These storied halls

History

The heritage of

Gilford Castle

Gilford Castle is a testament to Victorian elegance and architectural grandeur. It bears the marks of its many inhabitants, from the Dickson family, who commissioned its construction, to the Wrights, who lovingly restored and expanded it, infusing it with their unique character.

This estate embodies living history. It has witnessed generations pass, each leaving its mark, from its opulent beginnings to its present-day tranquillity. While that past lingers in its walls, Gilford Castle welcomes a new chapter as a place where tradition and modernity meet.

Discover how this bend in the River Bann came to be home to one of County Down’s most illustrious homes.

“Our parochial history is but Irish history, acted on a smaller stage.”

– E.A Myles, Historical Notes on the Parish of Tullylish, 1937

History

By the banks of the Bann

Snapshots in time

Gilford Castle Estate’s transformation

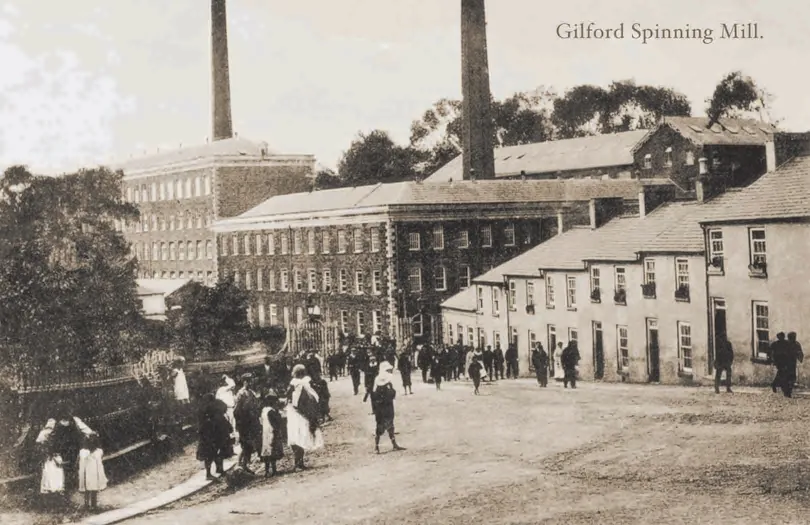

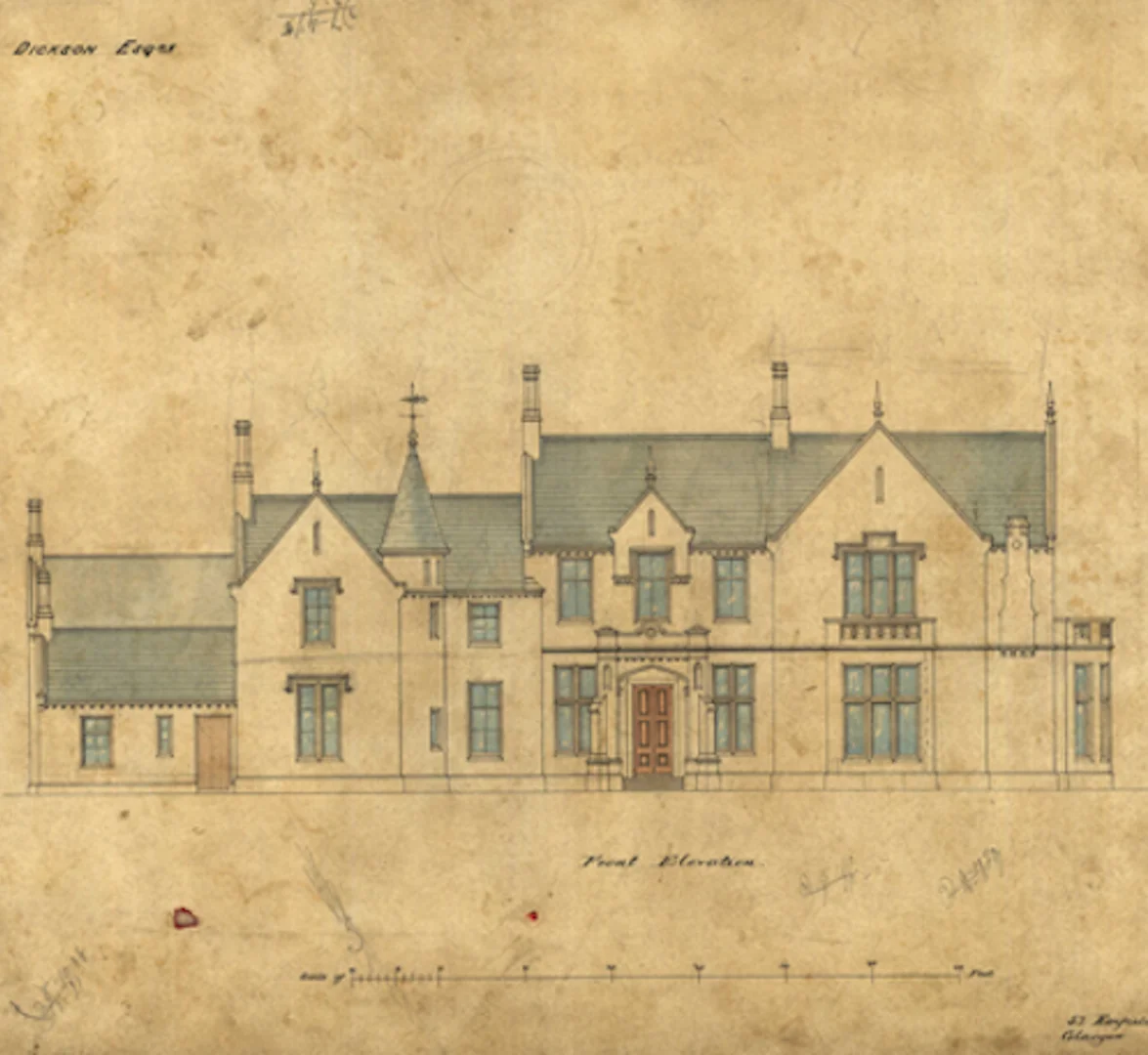

Gilford Castle was commissioned in the 1850s by Benjamin Dickson, a prosperous linen merchant whose family helped shape Gilford village’s industrial fortunes. Seeking a residence that reflected his success and standing, he engaged William Spence of Glasgow, an architect known for his romantic interpretations of the Scottish Baronial style.

Spence’s design combined rugged stone walls, turrets, and oriel windows with refined interiors rich in carved oak and stained glass. Built to overlook the River Bann, the house embodied mid-Victorian confidence — a blend of industry, artistry, and aspiration.

In 2019, Gilford Castle entered a new chapter. Under the Moffett’s care, every cornice, panel, and pane of glass was revived, restoring splendour to William Spence’s 19th-century design.

1

Entrance Hall

The Moffetts found Gilford Castle’s entrance hallway faded and timeworn, but restored it with the same attention to detail that characterised its original craftsmanship. They conserved the decorative plaster and oak detailing, revived the faux marble walls’ original tone, and reintroduced warmth through carefully chosen furnishings and lighting. Today, the space greets guests with the same rich welcome it afforded visitors more than a century ago.

2

Drawing Room

The Moffetts found the drawing room muted by age, but meticulously restored its original grandeur. They revived its ornate plasterwork and marble fireplace, reinstated period-appropriate wall coverings, and curated furnishings that echo the house’s Victorian refinement. The result is a room of warmth and composure, where every detail enhances the artistry of its 19th-century design.

3

Library

Gilford Castle’s cosy library overlooking the garden has been returned to its former warmth and depth. The Moffetts restored the original oak cabinetry and panelling, reinstated patterned wall coverings inspired by Victorian design, and introduced furnishings that bring texture and intimacy. Imagine sitting here on a rainy afternoon, the fire glowing, flipping through the pages of a good book.

4

Main Stairwell

The Moffetts have sensitively restored the main stairwell, conserving its original oak balustrade and stained glass while renewing the plasterwork and joinery with care. The space now glows with daylight filtering through the great windows, the warm light of the chandelier above, and the soft illumination of wall sconces on either side.

Look closely and you’ll see that the leaded glass bears the initials of Katherine Carleton, one of Gilford Castle’s most colourful former inhabitants.

5

Gentleman’s Lounge

Once stripped of its original character, the Gentleman’s Lounge has been completely reimagined yet continues to honour its Victorian proportions and features. The Moffetts restored the marble fireplace and intricate plasterwork, then introduced rich fabrics, period lighting, and bespoke furnishings to create an inviting space that balances refinement with comfort.

The walls feature hand-painted murals depicting Ulster’s historic castles, including Narrow Water near Warrenpoint and Dunluce on the north coast. Can you identify the others?

Contact

Embark on your journey

Staying at Gilford Castle Estate is a unique, exclusive experience. Reach out through our contact form and request a bespoke consultation so we can understand your requirements and provide you with a tailored experience.